“And when any one says that mankind must regard ‘the newest song which the singers have,’ they will be afraid that he may be praising, not new songs, but a new kind of song; and this ought not to be praised, or conceived to be the meaning of the poet; for any musical innovation is full of danger to the whole state, and ought to be prohibited.” Plato, The Republic, Book IV.

Once, there was a time when the South Coast, that hotbed of talent that has seemingly enthralled the rap nation with tempos, syncopation, slang, and rhythms for as long as many of today’s listeners can remember, toiled in obscurity.

Once, there was little more than Scarface, Bushwick Bill, and Willie D—the Geto Boys—slinging that Southern sound to the country’s extremities in Gotham, La La Land, and the largely untapped heartland in between.

And once, not so long after, Hanoch Yisrael, Khujo “Gun Club” Goodie, first generation Dungeon Family pioneer, the very pillar upon which the almighty Goodie Mob rose from and is yet today still standing on, had a dream.

“We was all spending the night at the Dungeon,” Khujo recalled about the studio that housed the seminal sessions for Outkast, Goodie Mob, Parental Advisory, Society of Soul and several other musicians and vocalists frequenting the southwest Atlanta lab. “We all slept on sleeping bags and whatever we could sleep on, sofas or whatever. And I had just had a dream about the [Goodie Mob] logo. I called Big Rube and was like this is the idea I had for the logo. Big Rube, he’s the one who drew the logo for us. That’s why you’ve got the black hands in the handcuffs; you’ve got the ‘m’ that’s depicting the silhouette of a man hanging. That shit was just symbolic of the struggle our people’s been going through: getting locked up and dying over basically bullshit.”

That vision, the solidification of the group’s logo, and Khujo’s efforts with the Mob’s 1995 gold-selling debut album Soul Food—just a year after fellow DF trailblazers Outkast reaped platinum with their debut, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzic—alongside the GB’s foundational footwork, kicked down all remaining barriers for the South to ascend to rap royalty. Whereas once the East and West coasts feuded for supremacy over what many dubbed the Hip-Hop nation, the South has unequivocally run rap for the past 20 years: showing signs of neither slowing, nor tiring.

But in that time (and for generations well before it, quite frankly) other things have been slow to change, things which may not be so coincidental to the rhyming reign below the Mason-Dixon line, or to the corporate entities funding the musical forays which somehow, someway, seem to trace back to that dirty dirty.

“In 2020 it’s not really bullshit that we’re dying over,” Khujo reflected. “Our people are dying over a lack of knowledge, man. They don’t know who they are, they don’t know who they came from, they don’t know that they have their own God that they serve. That’s not really bullshit; that’s really ignorance of wisdom right there. That’s why I like to come back, regroup, and do a little more building on some of the things that I used to rap about in some of my verses, where I can come back and really correct things like this. Because I was young at that time, and now I got a little bit more wisdom and I can kind of explain myself a little bit more.”

“The battle’s no longer physical, it’s from within/You live to die and you die to live again/” Khujo, “Decisions Decisions”, Muggs Presents… The Soul Assassins Chapter 1.

Contextualizing Khujo’s words, their magnitude and meaning, may take a while, especially for someone even remotely familiar with his oeuvre. This is, after all, the same dude who graced the national stage on his group’s debut single, “Cell Therapy”, urging you to “use that tool, between your two shoulders.” Such unexpected didacticism, the strains of ghetto knowledge found in the traces of emptied cigars and the residue of potent verses, has always been typical of the wordsmith’s work, whether solo or with his brethren. “Cell Therapy” introduced the country to a haunting, dystopian future, the likes of which even Nostradamus may have shied from, starting with the opening syllables of Khujo’s leadoff 16.

Such subjects and their reflections of a social commentary far too lucid for fabrication were artfully conveyed through a stark, rugged delivery endemic of the north west Atlanta streets—and woods—that raised him. In much of Goodie Mob’s early recordings Khujo rhymed first, assaulting audiences with an over-enunciated baritone that belied the deft nimbleness of a flow effortlessly panning from molecular biology to street survival, osmosis to gangsta shit. With him on the track, songs were suddenly serious, important, and more than just a little at odds with the carefree nature of much of today’s music—and even a fair amount of yesterday’s.

“I definitely want to make sure that people know that the name Goodie Mob was born in the trap of Howell Terrace,” Khujo intoned. “That’s in Southwest Atlanta. That’s how that name came about and it grew into what it is today: a socially, southern conscious Hip-Hop, country tune, rap group.”

To this day, the mob’s still mobbing. Khujo mentioned Sony’s set to re-release the group’s sophomore album, Still Standing, to commemorate it’s 20 year anniversary. Upcoming performances include dates in Chicago (July 20th) and Denver, as well as Atlanta’s A3C convention in October. With a stream of four singles released in the past couple of months—“38 Hot”, “Joogin et Pluggin”, “Blame it on Me (I Did That)”, and the thought provoking “YAH Fights”, Khujo’s working his way to his next full length solo release, currently titled Feed The Lions. The project includes production from Cee-Lo Goodie, Dr. Freak, Cashous Clay, Slime Nine and A1, with features from Goodie Mob’s Big Gipp and T-Mo, as well as songstress Erica Paige. A song with fellow ATLien Killer Mike is also in the works; the album should see the light of day this fall.

“It’s about just feeding the people as being the lions because people, especially in the Hip-Hop world, they’re just real hungry,” Khujo revealed. “You put an album out there they’ll just about eat that album up in maybe about a week. So I just want to feed them some meat. I think some of these songs I got qualify as some steak.”

The country rap tune movement spawned by Goodie Mob, the Dungeon, and the GB endures because it opened the floodgates for the current generation of southern musicians and emcees to even have a national spotlight streaming this way. But many of the central precepts of that movement—the struggle, the social commentary, its poignant truths—have been swallowed by a corporate machinery preoccupied with image and branding, subverting the music’s meaning to the establishment’s culture of instant gratification. Once, the narcissism of social media would’ve been dismissed as pure hype; today it’s how you get a record deal, climb Billboard, and grab the plaques to prove it. Any attempts to change this structure, to use the (rap) music medium as a mechanism for something other than consumption or greed, to publish tunes like “Yah Fights” which tackles spirituality, world history, and its postmodern repercussions, could upset the delicate balance of the socio-political underpinnings supporting contemporary popular culture.

“I was inspired to write that song “Yah Fights” because a lot of our black young brothers are getting shot down in the streets,” Khujo explained. “Even when somebody is calling to help them, police show up and end up killing the person that needs help. So it’s like, people don’t ask the question why are our people being shot down in the street? Why it’s not young Chinese men getting shot down in the street? Why it’s not young Japanese men getting shot down in the street?”

Readers Might Also Liked:

Hip-Hop Legends Goodie Mob, All Together, Sacrificing For The Culture

Hip-Hop Legends Goodie Mob, All Together, Sacrificing For The Culture

[STREAM] Freddie Gibbs Releases Surprise Album, ‘Freddie’

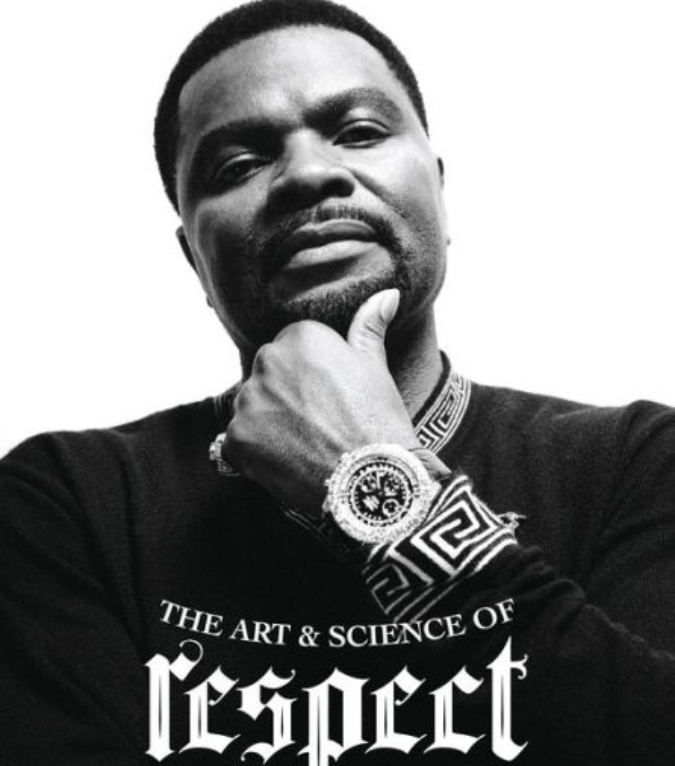

J. Prince Set To Release His Book, RESPECT

J. Prince Set To Release His Book, RESPECT